In September of 1959, the arriving Freshman Class of 1963 was treated to a few interesting lectures. One was by the famous mathematian Norbert Wiener (called "the father of cybernetics"), and another was a fascinating lecture on color vision by Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid.

But when both projectors were uncovered, we were startled to see a full-color image on the screen! The colors were not highly saturated - that is, they seemed a bit "washed out". Nevertheless, the full spectrum of colors was present, in complete contradiction to conventional color theory. Somehow, our brains had managed to assemble an approximation of the colors in the original scene. This work had been reported in a 1959 article in Scientific American, and Land later developed what he called his "Retinex Theory of Color Vision". Note 1 The lecture was a fascinating introduction to MIT.

Every student at MIT knew Professor Wiener by sight. He was the prototypical brilliant absent-minded professor. A classified 1942 monograph on signal transmission in a noisy environment was nicknamed "the yellow peril", because of the color of the cover and because few people could understand it. He wrote a book about his childhood called "Ex-prodigy". There are many stories about Wiener at MIT available on the web, so I won't repeat them here. Note 2 Just do a search on the terms ["norbert wiener" stories]. But I should caution you that they are not all true. In particular, the one about his not recognizing one of his own daughters was denied by his daughter Peggy Wiener Kennedy, who said, "Father may have been absent-minded, but he always knew who we were." Note 3 Back to Rota's lecture hall. Rota announced, "Professor Wiener will give today's lecture", and stood aside. Wiener lectured us on some obscure mathematical topic that had absolutely nothing at all to do with our class material. After receiving applause at the conclusion of his lecture, Wiener lit a cigar, and toddled off down the hall. Rota never said a word about why Wiener had been invited to lecture. But Wiener was getting on in years, and I imagine that Rota wanted all his students to hear the great Professor Wiener speak. Wiener died a few years later, in 1964.

I recall Shannon once describing how he was converting an old school bus into a camper for his family. In order to better visualize good ways of arranging the interior, he built a scale model of the bus. Its top could be removed, allowing him to experiment with various layouts of the interior partitions. Once the actual bus had been fully outfitted, he put the scale model bus on its kitchen table. However, this created an innaccuracy that disturbed him. So he bought a very small toy bus, and placed it on the kitchen table of the scale model bus. With a twinkle in his eye, Shannon then said to us, "And inside that toy bus, on the kitchen table, theoretically ..."

Upon arriving, I could immediately see that some of the audience members were not MIT students. Although they were fairly young, they were dressed in expensive three-piece suits. I sat next to some of them, so I could hear what they were talking about, to try to figure out who they were. They turned out to have been sent to the lecture by various New York brokerage firms, who had evidently seen the Tech Talk announcement, and wanted to see if Shannon's research was anything useful. As the lecture started, they all took pads of paper out of their leather attaché cases, so they could take notes to bring back to their firms. The trouble was, Shannon immediately began filling the blackboards with differential equations. I watched as the brokers' jaws dropped. They seemed unable to even take notes to be interepreted later - all the boards were covered with integrals and summation signs and Greek letters that they didn't even know how to copy accurately. I wondered how their reports would go over back in New York. Note 5

From 1961 through 1966, Charles Townes was Provost of MIT. Some time during that period, I saw an item in Tech Talk announcing a lecture at MIT by Dennis Gabor. I arrived early, and sat in the front row. Gabor was waiting at the front of the room to start his talk, when another early arrival showed up - Charles Townes. Townes introduced himself to Gabor - I got the impression they had never before met. They shook hands right in front of me - the inventor of the hologram, and the man who had invented the laser which had turned his theoretical invention into a reality. Townes won the Nobel prize in physics in 1964 (shared with Nikolay Basov and Alexander Prokhorov). Later, in 1971, Gabor would be awarded the Nobel prize in physics for his work on holography. Note 6

Some time later, another student asked me whether I had had the good fortune to see the artist, Alexander Calder. For that was indeed who it had been. After checking out the work and pronouncing himself satisfied with the installation, Calder had been signing it as I passed by, using a welding torch to create a raised signature on the steel. The photograph to the right shows a close-up of his signature.   Note 1: An interesting description of Land's accidental discovery of this effect can be found here. [return to text] Note 2: OK, here's what I've always thought of as the best of the stories. Back when Wiener actually had to teach Freshman math courses, a student asked him how to solve a particular problem that had been assigned for homework. Wiener read the problem, wrinkled his brow for a few minutes, and, having solved it in his head, wrote the answer on the blackboard in the front of the room. This was no help to the student, of course. But not wanting to insult the famous professor, the student cagily asked if there was another way to solve the problem. Wiener thought this was an interesting question, mumbled to himself a bit, paced back and forth for a while, and then again wrote an answer on the blackboard. Seeing that it matched the first answer, he smiled with satisfaction. At this point, the story goes, another student at the back of the classroom said, "Professor Wiener, I've got a third way to solve the problem." Wiener allowed as he didn't see any other way to go about it. The student held his head in his hands, paced rapidly back and forth for a while, and then wrote the same answer on the blackboard at the rear of the classroom (many MIT classrooms had blackboards both at the front and the back of the room, so you were less likely to run out of space to write). The class laughed, but in the front of the room, Wiener was shaking his head from side to side. "What's wrong?", asked the student. "I got the right answer, didn't I?" Wiener replied, "Oh, you got the right answer, all right, but your method was all wrong." I should say that the two times I heard Wiener speak, he had no problem bringing himself down to the level of his audience, and making himself perfectly clear. [return to text] Note 3: Jennings, Karla. The Devouring Fungus: Tales of the Computer Age. New York: W.W. Norton, 1990. ISBN 978-0393307320. p.55. [return to text] Note 4: MIT Tech Talk was distributed all over the campus, and it was well worthwhile to pick it up and peruse the weekly calendar. It was possible for non-MIT readers to subscribe to receive it by mail (that is, by what is now called "snail-mail"). It was published in paper form through 2009, but is now available only on the web. [return to text] Note 5: In his talk, Shannon showed a way of profiting from random fluctuations in a stock's price, regardless of whether the overall trend was up or down. The method depended on being able to buy and sell quickly, without having to pay any commissions. If I recall, the upshot of all the math was that all you had to do was to keep a fixed amount of money invested in the stock. That meant that if the price dropped, you would buy some more, and if it rose, you would sell some. Intuitively, this means that you are buying low and selling high, and indeed, all the math showed this to be an optimal strategy. I don't know if the conclusion could have been of practical value to the brokerage firms. It was useless to me, because it assumed no commission charges. But a brokerage firm that was a member of the exchange might well be able to trade commission-free. [return to text] Note 6: Gabor's lecture that day was on a theoretical system that could be used to show three-dimensional movies without requiring the wearing by the viewers of any sort of glasses. But it required the use of a special spherical screen, with an emulsion that could develop reflective layers in depth, perpendicular to the plane of the emulsion. Although this could be done with a process developed by Gabriel Lippmann, the reflectivity of these emulsions at the time was not sufficient to create a workable screen, nor was it possible to fabricate a screen of movie-theater dimensions using Lippmann's technology. It seems that Gabor had a habit of proposing theoretical inventions that the technology of the time couldn't actually realize. [return to text]  |

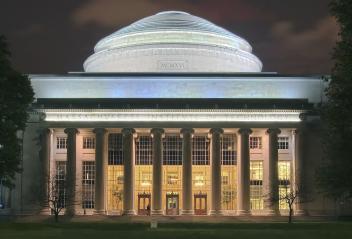

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology ("MIT") was and is a remarkable place, full of remarkable people. This entry recalls some of the well-known people I crossed paths with during my 11 years there, between 1959 and 1970.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology ("MIT") was and is a remarkable place, full of remarkable people. This entry recalls some of the well-known people I crossed paths with during my 11 years there, between 1959 and 1970.

Land (shown to the right) projected an image onto a large screen in the otherwise darkened Kresge Auditorium using two projectors, their images superimposed on the screen. One of them showed a black and white photograph of a still-life. The other projected another black and white image that had been taken through a red filter, and was projected onto the screen through the same red filter. Using his hand, Land covered first one projector and then the other. With the red-filtered projector covered, we saw a monochrome ("black and white") photograph of the scene. With the white-light projector covered, we saw a similar monochrome photo, but in tones of black-and-red instead of black-and-white.

Land (shown to the right) projected an image onto a large screen in the otherwise darkened Kresge Auditorium using two projectors, their images superimposed on the screen. One of them showed a black and white photograph of a still-life. The other projected another black and white image that had been taken through a red filter, and was projected onto the screen through the same red filter. Using his hand, Land covered first one projector and then the other. With the red-filtered projector covered, we saw a monochrome ("black and white") photograph of the scene. With the white-light projector covered, we saw a similar monochrome photo, but in tones of black-and-red instead of black-and-white.

As for Norbert Wiener (shown to the left), I heard him talk twice while I was at MIT. At some point during my undergraduate years, I took a course in Probability Theory given by Gian-Carlo Rota. Rota was a very amusing lecturer - he once described another MIT mathematician as "one of the great probabilists at MIT" (he stressed the second syllable, pronouncing it "pro-BA-bi-lists"). Arriving for the lecture one day, we found Institute Professor Norbert Wiener standing in front of the room.

As for Norbert Wiener (shown to the left), I heard him talk twice while I was at MIT. At some point during my undergraduate years, I took a course in Probability Theory given by Gian-Carlo Rota. Rota was a very amusing lecturer - he once described another MIT mathematician as "one of the great probabilists at MIT" (he stressed the second syllable, pronouncing it "pro-BA-bi-lists"). Arriving for the lecture one day, we found Institute Professor Norbert Wiener standing in front of the room.

In his writings on Cybernetics, Wiener always emphasized his indebtedness to Claude E. Shannon's information theory, developed in 1948-1949. Shannon (right) had earlier put forth Boolean algebra for use in the design and analysis of digital circuits. This latter work was done, astoundingly, in his MIT Master's Thesis, which some have called the most important Master's Thesis of all time. Both these contributions were fundamental developments in Computer Science. I had the great fortune to have Shannon as a professor in a two-semester electrical engineering projects course.

In his writings on Cybernetics, Wiener always emphasized his indebtedness to Claude E. Shannon's information theory, developed in 1948-1949. Shannon (right) had earlier put forth Boolean algebra for use in the design and analysis of digital circuits. This latter work was done, astoundingly, in his MIT Master's Thesis, which some have called the most important Master's Thesis of all time. Both these contributions were fundamental developments in Computer Science. I had the great fortune to have Shannon as a professor in a two-semester electrical engineering projects course.

Dennis Gabor (left) was a Hungarian-born electrical engineer, born in 1900. Among his many accomplishments, he invented holography in 1947. His invention was largely theoretical, as making holograms depends on having a source of coherent light, which didn't exist in 1947. Gabor experimented with a heavily filtered mercury arc light source, but was not able to obtain the coherence length he needed. Thus, his invention was of only academic interest, until the later invention of the laser.

Dennis Gabor (left) was a Hungarian-born electrical engineer, born in 1900. Among his many accomplishments, he invented holography in 1947. His invention was largely theoretical, as making holograms depends on having a source of coherent light, which didn't exist in 1947. Gabor experimented with a heavily filtered mercury arc light source, but was not able to obtain the coherence length he needed. Thus, his invention was of only academic interest, until the later invention of the laser.

In 1951, Charles Townes (right) conceived the idea of the MASER, an acronym for Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The idea was brought to fruition in 1954, and in 1958, Townes and Schawlow showed theoretically that masers could be made to operate in the optical and infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Taking off from the MASER, they called the optical version of the device a LASER, for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The subsequent creation of lasers in many portions of the optical spectrum finally provided the coherent light needed to make Gabor's dream of creating holograms a reality.

In 1951, Charles Townes (right) conceived the idea of the MASER, an acronym for Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The idea was brought to fruition in 1954, and in 1958, Townes and Schawlow showed theoretically that masers could be made to operate in the optical and infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Taking off from the MASER, they called the optical version of the device a LASER, for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The subsequent creation of lasers in many portions of the optical spectrum finally provided the coherent light needed to make Gabor's dream of creating holograms a reality.

There are many works of art around the campus, some by well-known artists. The photo to the left shows Alexander Calder's 12-meter (40 foot) high stabile "La Grande Voile" ("The Great Sail"). It was a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene McDermott, and stands in McDermott Court. McDermott Court, in front of the Cecil and Ida Green Building for the Earth Sciences, experiences high winds. It was rumored that "La Grande Voile" was commissioned to deflect these winds, but MIT denies that was its purpose. A scale model of the sculpture was subjected to wind-tunnel testing, but MIT administrators insist that the tests were only to ensure that the sculpture could stand the high winds in the court.

There are many works of art around the campus, some by well-known artists. The photo to the left shows Alexander Calder's 12-meter (40 foot) high stabile "La Grande Voile" ("The Great Sail"). It was a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene McDermott, and stands in McDermott Court. McDermott Court, in front of the Cecil and Ida Green Building for the Earth Sciences, experiences high winds. It was rumored that "La Grande Voile" was commissioned to deflect these winds, but MIT denies that was its purpose. A scale model of the sculpture was subjected to wind-tunnel testing, but MIT administrators insist that the tests were only to ensure that the sculpture could stand the high winds in the court.

I watched it being erected in 1965. Passing by one day after it had been completed except for the final painting, I noticed a man working on it with a welding torch. I couldn't see his face, of course, because he was wearing a welder's helmet. He seemed to be doing something on the side of one of the steel "sails". I assumed it was some operation related to putting up the sculpture.

I watched it being erected in 1965. Passing by one day after it had been completed except for the final painting, I noticed a man working on it with a welding torch. I couldn't see his face, of course, because he was wearing a welder's helmet. He seemed to be doing something on the side of one of the steel "sails". I assumed it was some operation related to putting up the sculpture.